Last month on the Facebook Golden Age Detection page, the great blogger Xavier Lechard opened up the proverbial can of worms, and I have this to say about that!

First, though: if you are a GAD fan like me (and still brave membership on Facebook) yet do not belong to this amazing group . . . well, frankly, I don’t understand you. Finding this page was a lifeline for this classic mystery fan who had pretty much gone it alone these many years. Currently 983 members strong, the Golden Age Detection group shares favorite books and new discoveries, posts fascinating articles, intriguing questions or observations, and in all sorts of ways engages in a stimulating trade of ideas and opinions. It’s an active group and, naturally, this many people are occasionally bound to find themselves in disagreement, not only in our tastes, but in our perceptions of what is what, who is who, and – for all you impossible crime fans – how is how in classic mysteries. But when Xavier posed the seemingly innocuous question, “(What is) the silliest solution in a GAD mystery?” I don’t think even he was prepared for the, ahem, shitstorm he would stir up.

The definition of silly is: having or showing a lack of common sense or judgment; absurd and foolish.Synonyms include stupid, idiotic, brainless, witless . . . you get the idea. On paper, this sounds pretty bad, but I think most of us have a more benign impression of silliness as something childishly funny. The Three Stooges were silly. Bennie Hill was silly. The Muppets are silly. Clowns and mimes are “silly.” (Well, maybe there is a tinge of malevolence to be found at that!)

We all got what Xavier meant, and it had nothing to do with witless humor. He was asking when does a classic mystery solution stretch beyond the pale of its acknowledged unreal reality, its exaggerated depiction of a murderous situation, into the ridiculous? And what the answer turned out to be, if you could read between the lines of our knock down drag-out fight animated discussion was – pretty much all the time! For we couldn’t come to an agreement about any title!

Silly . . . . . or true?

Silly . . . . . or true?

Although I contributed to Xavier’s post, I was struck with a nagging worry that here we were falling right into the trap of the GAD naysayers who have long dismissed the whole canon as an absurd depiction of the committing and solving of crimes. The Golden Age authors never took it upon themselves to tackle crime-solving in a realistic way. Even the more procedural-type sleuths always got their man, and the suspects, methods and clues were rarely as banal as those found in real life.

As I pondered the motivations of early 20thcentury mystery writers, I was reminded of my film class, where I teach some of the history surrounding the invention of the art form. I discuss three pioneers from France: the Lumière brothers and Georges Méliès. Auguste and Louis Lumière sought to invent a device that could allow French audiences to observe the detailed realities of life. Their films had titles like “The Arrival of a Train” and “Employees Leaving the Lumière Factory.” Méliès, on the other hand, saw film as an art form that could take us out of our humdrum real lives by allowing us to witness pure fantasy on the screen, such as the sight of a rocket landing on the moon – and poking it right in the eye!

To my dismay while following Xavier’s post, Agatha Christie bore the brunt of the discussion. On the spectrum of realism, I think Christie tends to fall somewhere in the middle. While her plots have a touch of Méliès in them, the trappings of her stories – character, setting, social custom – really do give us an accurate impression of the lives of the British middle and servant classes during the first half of the 20thcentury. Yet while titles by other authors received brief mention (Allingham: The Tiger in the Smoke. Brand: Suddenly at His Residence. Bude: The Cornish Coast Murder. Carr: The Crooked Hingeand The Problem of the Wire Cage.Marsh: Death and the Dancing Footman. Queen: The Greek Coffin Mystery. Wells: Murder in the Bookshop), Christie titles got mentioned again and again: Murder on the Orient Express, Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, After the Funeral, Sparkling Cyanide, Evil Under the Sun. . .

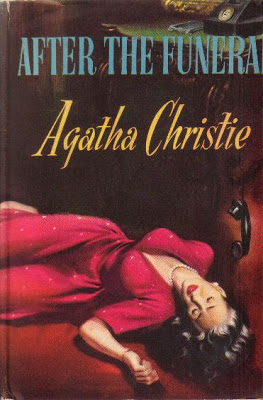

I resisted countering some of the arguments against these titles as long as I could. But since discussing Christie has become my métier on this blog, I finally had to speak out, especially when my beloved After the Funeral was mentioned. The reasoning behind those who would label this title “silly” was that the murderer’s plan seemed over-the-top ridiculous. Without giving anything away, the goal of anymurderer is to get away with their crime. The goal of a Golden Age villain is to do this with panache!

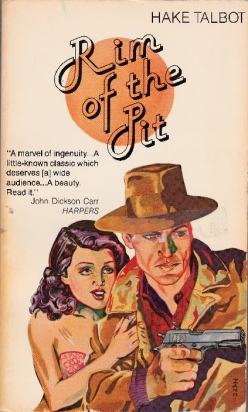

Misdirection was the tool of many an author, but Agatha Christie was its mistress. When Hake Talbot begins his best novel, Rim of the Pit, with a séance, he loses no time in exposing the psychic as a fake – and then doubles down on the suggestion that the subsequent murders are the work of a vengeful Native American spirit called a wendigo. Are we ever meant to take seriously the idea that an Indian werewolf is at fault here? Of course not. Talbot piles on the fantastical incidents – strange footprints, flying beasts, crimes that no human could have possibly committed – and we wait with bated breath for some natural explanation for all these miracles. It’s the code of the impossible crime writer. It’s the reason that a certain John Dickson Carr title – you know the one I mean – is so very vexing to many of his fans.

Christie introduced the supernatural and played with the impossible on occasion. (I hope to get more deeply into this topic sometime this summer.) But what she excelled in was a more prosaic form of misdirection. Christie – and, by extension, her murderers – could make you look over your right shoulder for clues and then prove beyond doubt that the truth lay over your left shoulder. She could toss a bomb in the most innocuous phrase or convince you that the date that Suspect X arrived was the salient fact when the trueimportance lay in the butler having to walk across the kitchen to see the calendar.

Within the imaginative, Méliès-like world of GAD fiction, the killer in After the Funeral has a very good reason to do what they do in order to effect their plan. A few choice actions, and this killer has the police chasing off in all the wrong directions. Now, since this plan is directly responsible for Mr. Entwhistle calling in Hercule Poirot, one could argue that the killer’s cleverness was their own undoing – but this is precisely what we are told about killers in one GAD novel after another!!! I accept this element of artifice. It leaves me with the impression that After the Funeral is a brilliant piece of work!

However, it is not my intention to argue my point over all these titles. The people who suggested they were silly are, every one of them, devoted and intelligent fans of the genre who are entitled to their opinions. It did make me think, however: does Christie ever get so carried away that her plots border on the ridiculous?

Well, there are the thrillers, of course, but arguing against them is hardly fair. All thrillers have an element of science fiction or Gothic horror in them. Vestiges of Edgar Wallace and Sax Rohmer, of Wilkie Collins and Poe’s orangutan, can be found in every tale of spies and adventurers from John Buchan to Robert Ludlum. Christie was no exception. She loved foreign conspiracies and evil masterminds. A few times, her passion paid off in spades: The Pale Horse is wonderful, and the secret of The Seven Dials Society is a delight. But all those “young Siegfrieds” of They Came to Baghdad and Passenger to Frankfurt? The secrets behind the leper colony in Destination: Unknown? Bah! Humbug!

But we weren’t talking about the thrillers in Xavier’s post. So let me offer a few suggestions as to where I believe Christie’s cleverness goes off the rails, starting with the one title that came up in our discussion over and over again. Murder in Mesopotamia (1936) provoked more response than any other, and to my great surprise, opinions veered so wildly that battle lines were nearly drawn. I’m not going to spoil the book for you here, but if you haven’t read it, I am going to describe it in enough depth that your enjoyment coming to it for the first time could be affected.

There is much to like about MiM. Its setting, an archaological dig in Iraq, is well rendered. It was an environment of which Christie had much practical knowledge. She based the main victim, Louise Leidner, on real-life archaologist Katherine Woolley. It was Woolley and her husband, Leonard, who had invited Christie to stay with them at Ur and introduced her to her future second husband, Max. Katherine was a fascinating woman whose unconsummated marriage to her husband was done to preserve a semblance of respectability on a dig full of men. Some authorities state she was a hermaphrodite! No matter: what is conclusively true is that she was both an invaluable aide in Sir Leonard’s work and a difficult woman to be around.

Christie (perhaps) exaggerated Katherine’s most mercurial qualities when she created Louise, a restless, neurotic woman whose sharp tongue, powers of observation, and desire for a passionate life make her the ideal GAD victim. Unfortunately, she is the most interesting character in the book, and when she dies, much of the narrative excitement dies with her. On the plus side, MiM is arguably Christie’s strongest attempt at an impossible crime novel: Louise is found in her bedroom with her head crushed in but with no sign of a weapon. She was seen going into her room alone. Up through her death, her doorway was under constant surveillance and no one was seen entering. The only window was locked and barred.

The solution to this situation is not the problem with this book; indeed, it is a perfectly fine solution, one that not only explains how Louise was killed but why the killer chose to make this a locked room murder. No, the problem with MiM is that the solution utilizes a device common enough in mystery fiction that here is so unbelievable as to be ludicrous. This was one of the first titles to pop into my head when Xavier posted his question, and I was not the only one. Imagine my surprise, then, when we found ourselves engaged in a fervent argument surrounding this device, with some people positing vociferously that, given the personality of the victim and allowing for certain elements of the time period that I don’t want to get into here, there was nothing “silly” about this plot point.

Classic mysteries are fantastical creatures. For every killer who simply shoots their spouse, drops the gun and runs, (how lucky for them that their neighbor then came in and picked up the gun . . . just as the police arrived) – for every one of these, there are the clever criminals seeking to build a better mousetrap, just like that marvelous game. Indeed, I think board games make a wonderful metaphor for the classic mystery. The killer is the designer of the game. The boards vary in appearance according to the villain’s need: an island shaped like an Indian, a castle with a locked tower, a charming country mansion. The character pieces that move along the board are as varied as those in Monopoly, and extra game parts – the wacky devices that kill invented by John Rhode; the maze of false alibis from Christopher Bush, Ellery Queen’s Challenge to the Reader –serve to make each game more varied and exciting.

It doesn’t always work, and as we GAD fans have all come to realize, prolific authors like Christie or Carr or Queen are bound to hit a sour note that renders a few titles, well, silly. Besides Murder in Mesopotamia, here are six Christie novels that, to my mind, are deserving of this dubious accolade, one from each decade she published. (Not a bad percentage, if you ask me.)

The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928)

Is it worth reading? Of course. Some wonderful characters embark on this misbegotten adventure: Katherine Grey is a marvelous creation, possibly the second-best Watson with whom Poirot worked (Mrs. Oliver was the first), and her Riviera relations are wonderfully awful (or awfully wonderful?). But Blue Train suffers from a vast infusion of “thriller-itis,” compounded by Christie’s emotional distress at the time of writing. The short story “The Plymouth Express” is padded beyond belief, and the idea of “Le Marquis,” a masked jewel thief/murderer, is silly from the get-go. There are some clever deductions about the time of death; otherwise, to be honest, I don’t recall much of Poirot’s work here. All the best ideas of this murder plot can be found in the short story; despite some entertaining passages, the rest is dross.

Dumb Witness (1937)

This is a highly readable and enjoyable novel, with all the trappings of a fine mystery. Again, it is based on a superior short story, “The Mystery of the Dog’s Ball,” which we can thank John Curran for making available in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks. The prose, the characters, the repartee between Poirot and Hastings, especially in a funny scene where they portray – well, they resemble a couple trying to buy a house – all of this is worthy of your time. I don’t even mind the way Christie weaves the supernatural into this, although she does the séance bit so much better in The Sittaford Mystery. Her knowledge of poisons comes into play in a nicely creepy way here.

No, it’s the clue that breaks the camel’s back that makes this novel so damned silly. I really don’t intend to spoil anything here, so I’ll make this as oblique as I can be: there is an item that is presented as a clue against X, which discerning readers, applying a bit of logic and memory, can spot as an incriminating factor against Y. But this item has no business being where it is found. The very thought that it would be is so completely . . . SILLYas to take the whole book down several notches in estimation.

Sparkling Cyanide (1945)

Are we sensing a pattern here? We have yet another novel stretched out from a short story (“Yellow Iris”). But this is the 40’s, and the strength of Cyanide is in its characterization. The opening is pure gold, as six people who were present at the fatal birthday dinner for Rosemary Barton each reminisce about the events leading up to her apparent suicide. The rare appearance of Colonel Race is also welcome, although just as in Cards on the Table, he is ultimately relegated to a secondary position on the sleuthing chain.

No, once again, a book is done in by the most ridiculous of events. I can’t call it a clue. Call it an . . . accident? Yet for this accident to work, the entire cast – a group of people shown in the aforementioned opening chapters to be sensitive and observant – have to be so oblivious to their surroundings as to defy reality. And yet, for the events to unfold as they must, oblivious they must be . . .

Dead Man’s Folly (1956)

Let’s be fair here: while I actually do enjoy the earlier titles, this one has never been a favorite. The set-up should be brilliant: Mrs. Oliver is hired by Sir George Stubbs, a boorish country squire, to create a murder game for the local fete. Her intuition goes haywire, and she summons Hercule Poirot down to the country to see if something horrible is afoot.

Of course there is, but it all seems more contrived and cliched than Mrs. Oliver’s much more hilarious Murder Game, and the central trick is both reminiscent of Murder in Mesopotamia and far more dully employed than in the earlier book. Pieces of the plot seem dragged from earlier works, and – once again! – Christie wrote a shorter version of this one – Hercule Poirot and the Greenshaw Folly– which I have never read but which is available in case you’re interested. Still, you would miss the meta-fictional joys of Mrs. Oliver’s Murder Game plot, Christie’s nudge to readers that these tales can get ridiculous because we seem to like them that way!

The Clocks (1963)

There’s both too much and not enough going on in this surprisingly dull novel. A silly mishmash of international espionage and domestic murder (some may argue that Cat Among the Pigeons also suffers from this problem, but I love the girls of Meadowbrook School enough to forgive the excesses of Ramat), the novel suffers from too many cardboard characters and some shockingly weak plot points. (Does anyone remember why the clocks are present?)

Colin Lamb, the blind lady and one little girl are the bright spots in another grab bag of old ideas. The one saving grace should be Poirot’s discussion of his upcoming magnum opus on crime fiction. But instead of some true meta-moments, Christie chickens out and gives almost all of Poirot’s literary subjects fake names. Evidently, it has become something of a game to figure out who is who here.

Elephants Can Remember (1972)

It’s almost unfair to include this one. In fact, JJ recently argued its good points. Any time spent with Ariadne Oliver is okay by me, even if we have to deal with the likes of Folly, Third Girl or this title. But Christie’s powers were very much on the wane here, and the result is, logically, highly problematic. The time frame, the varying ages of the main characters, the vagueness of everyone’s memory over something that happened sixteen years earlier – compare this to the sharpness of everyone’s memory after a similar passing of time in Five Little Pigs; has there been a lot of drug use since then?

But the silliest aspect of this whole affair lies in the killer’s expectation that their crime will have a certain result. And even if everybody involved in the case fell out of a plane in the meantime and got amnesia, I cannot believe that nobody saw through this particular – thing! It defies belief, even in the gloriously insane world of GAD crime.

So there you have my six nominations for TSC – Truly Silly Christie. And you know something? I still recommend you read them. They do not show Christie at the height of her powers – far from it! Yet there are characters, scenes, and plot elements worthy of your time in each of them. In fact, I still re-read them all on a regular basis.

Isn’t that silly of me?

Brad, I don’t know if I made it clear that my criticism of After the Funeral wasn’t a suggestion that it was one of the silliest solutions in the Christie oeuvre (and indeed, while its not my #1 favorite Christie novel, it only trails behind ATTWN, FLP, and DOTN for me), but merely an agreement with another commenter that if the culprit had just committed a halfway subtle poisoning of Cora, it very likely (considering her age and also her eccentricity) would’ve escaped any investigation at all as an unnatural death— andultimately would’ve been a much less risky way to achieve the killer’s aims. I consider it a valid objection— for claims that a character wouldn’t do something are really as valid as those that a character couldn’t do it (as your other examples suggest). At the same time, I consider it a brilliant misdirection.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No, no, you made yourself clear at the time, Scott. I think I responded that Louise Doyle could have simply fallen off a pyramid. The killers’ scheme in Evil Under the Sun or A Caribbean Mystery is pure artifice. Does nobody KNOW these people or notice the pattern??? But we accept this artifice as part of the GAD package. If the killer in AtF had taken the “easy” route, there would have been no book!

LikeLike

But Brad, what I’m saying is that although we make allowances for certain artificialities of fiction, we do ultimately require that detective stories reflect the realities of our world, including those of understandable human motivation and behavior. For instance, we may accept that someone will work for weeks on a clever plan so that they can acquire $5,000,000, but will we be satisfied with a story that tells us someone worked for 27 years on a plan to acquire a $45 coffee table? No— and the only real difference is that one much more closely reflects what we accept as believable human behavior (which is why the monetary motives in Agatha Christie novels much more often involve hundreds or thousands of pounds rather than five or ten). Even the motive for the deception in After the Funeral is retrospectively easy to understand and identify with— it throws suspicion away from the culprit, which is something a culprit would want to do.

But when the liabilities of a culprit’s plan outweigh its benefits, we must rightly recognize it as either a flaw in the logic of the culprit (which we can somewhat do in the case of the culprit in ATF) or of the work itself. And there are things that can be done to minimize such logical flaws. For instance, if Aunt Cora had been characterized as younger and in more robust health (even if just as eccentric), killing her off in a way that would be taken as natural death would not have been nearly as viable option, and thus the route taken by the culprit in the novel would been more justifiable.

Because “otherwise there would be no book” ultimately provides a slippery slope for the justification of artifice— we don’t really want to use it to defend the $45 coffee table plot, do we? And we don’t require extreme voyages from recognizable situations to provide interesting, complex puzzle plot scenarios, either. The reason Five Little Pigs (which I’ll admit is not perfectly unflawed in this respect either) is held in such admiration is not only because its characterizations are more like those of literary novels, but because they (generally) justify the behavior of the characters.

I read in some comment thread that “realism has no place in detective fiction.” But if that were the case, we should have no problem with the aspect of Murder in Mesopotamia that troubles us, either. No, I suggest it’s a matter of degree (and of differing levels of subjective acceptance). Mind you, I’m not arguing that realism is the desired aim of the genre. Merely that our reader satisfaction is dependent upon a certain reflection of it.

LikeLike

I don’t think we disagree about generalities, Scott, just about After the Funeral. (And I know you like the book, too, I really do.) The killer here believes, with some justification, that they cannot get what they want through normal means. Their frustration is exacerbated by their current condition, and each new element of that is a slap in the face. I believe there was a lot of hatred and greed brewing in that killer, as well as a lot of overweening vanity. It’s the perfect brew for a GAD killer. Furthermore, I think some of the joy I experience each time I read this is the very outrageous unbelievability that a person WOULD act this way. Yup, not realistic, but highly entertaining . . . and I buy it completely within the framework of the GAD world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You know va lot more about Christie than I do, Brad, so I’ll defer to the facts you lay out. I will say, though, that even when Christie goes too far in her solutions, what I think makes a lot of it work is that there is also a lot of the prosaic in her work as well. I’ve often wondered whether she was aware of taking a solution too far and was having a little fun. Just my wondering…

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s something to enjoy in every one of the books I mentioned here, Margot. So yes, it isn’t always the solution where Christie scores her best marks. I don’t think people give her enough credit for that, either!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vague SPOILER for Murder in Mesopotamia below:-

I may be the only person in the world who thinks MiM has a nice solution. After all, people change a lot in 15 to 20 years……

I’ll have to disagree with The Greek Coffin Mystery as well. It’s one of the benchmarks of the Golden Age in my opinion. Excellent misdirection, wonderful clueing, three great false solutions and a completely surprising but perfectly logical murderer. Nothing silly about it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was the first Queen mystery I ever read, Neil, and it remains one of my favorites!! Reading someone’s dismissal of it as “silly” was painful, to say the least. Like you, I disagree entirely.

LikeLike

I like MiM and will be reviewing it soon at Countdown John’s Christie Journal and hoping to make a reasonable case for the defence. Coincidentally I will also soon be reading The Greek Coffin Mystery so I hope it’s not silly either!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I promise, promise, PROMISE you, John – TGCM is not silly in the least.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like MiM — an early one for me, sure, but I remember it very fondly. And, I thought the idea behind the silliness, assuming we’re talking about the same aspect, is that it was supposed to be silly, as in the victim is required to go “Oh, come off it…” in order for it to work. But maybe I misremember.

I’ll be looking forward to your post on it, John, even if my own input will be limited to a vague haze of imperfect recall.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope John’s post will disperse the haze because, based on what you said, we’re talking about two different things. Though your vague memories may mask the truth, what I’m talking about is a marriage of two minds!

LikeLike

Hang on…hang on…I feel like — like — like there’s a memory I can’t quite get at… But, sure, it would appear we’re not talking about the same thing. Hmph. I shall simply have to review this when I reread MiM about 2 years from now…

LikeLiked by 1 person

So funny! As I read your comment, I’m watching an episode of Criminal Minds, and they’re using their special memory recall strategy on a witness! We should try that!!!

LikeLike

I don’t claim to be as knowledgeable about whodunnits or murder mysteries (or whatever you want to call them), but I’ve picked up a few things along the way. The most fascinating thing about them is how different they are from thrillers (a related genre). In a thriller, the pace will typically rise at the climax. In a murder mystery, it will slow down. The final chapters (sometimes the penultimate chapters) are filled with long dialogues that will explain and reveal what happened and whodunnit – often in a sterile setting (libraries come to mind). Yet, fans will tell you that these climaxes are tense. For an experienced reader, this tension is all about the anticipation of how disappointing the solution will be. You’ve sat through a (hopefully) bewildering series of events and now you say to the author, “Don’t let me down too much.” All of the solutions are ridiculous. Every single one of them. Personal anecdote – When I decided to write my first book, I set a target date. Then, I read as much as I could before that date. The last thing I read was Raymond Chandler’s preface to The Simple Art of Murder. I was devasted. He eviscerates the genre. Worst of all, everything he says is true. The timing, the wonky motivations, the terrible police representations, all of it. I went to bed after I read it, thinking about how I had wasted my time. Then a wonderful thing happened. The next morning, I was inexplicably enthusiastic again. I realized that the appeal came from a lot of the things he was criticizing. Some of the solutions go a bit far off the rails, but all of them fall short of the demands of realism. These books have their own interior logic. Of course, I have read some that I simply couldn’t buy, but that was less about the silliness of the solution and more about how the solution betrayed the logic of the book. If that makes sense. Rim of the Pit is a wonderful example. Every solution in that book is ridiculous… and wonderful. Sorry for pontificating. It’s just that I’ve had this discussion with myself so many times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with what you say, James, and I particularly like the way you point out the differentiation in structure and pace between the thriller and the whodunit. Being the more “cerebral” sub-genre, the whodunit faces the challenge of imparting information rather than action, and that runs the risk of being boring. The thriller is like the Everready battery that keeps a’going and a’going, but there still needs to be some logic to the way people act and react there or the whole thing caves into silliness.

I have not made, nor will I ever make, a case for GAD mysteries being realistic or lacking something because of their lack of reality. They’re supposed to be a little bonkers in order to take us away form the mundane cruelty of real evil. Thinking of all the schemes going on in Goodnight, Irene, I can’t imagine enjoying it as thoroughly if any one of your characters decided to behave like a “real” person. But that’s the point of this most artificial of genres, and I’ve always thought that Chandler was a bit of a louse. Just say you don’t like the stuff, Ray, rather than trying to “prove” it’s bad by stating all the things that make it wonderful!!

LikeLike

I skimmed this as I don’t want any taint on the books that I haven’t read – and I haven’t read most of them. That’s a lot to look forward to.

As to my “silliest solutions to a GAD mystery” votes:

1. John Dickson Carr – Night at the Mocking Widow – I hate this book, but I love the solution. With that said, it’s just completely comical to the point that you can’t take it seriously.

2. John Dickson Carr – Seeing is Believing – In this case I absolutely love the book, but unfortunately it’s dragged down by a solution that seems like it was stolen from a road runner / coyote cartoon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Turnabout is fair play! Now I have something to look forward to – I guess? – When I get to these two titles in my ACDC celebration.

LikeLike

The goal of a Golden Age villain is to do this with panache!

This, for me, sums up GAD perfectly: so long as I sold on the panache behind it all, I’m happy. The examples you list above all feel weirdly false in the setting, which is why they stand out. Conversely, the killer in And Then There Were None runs a scheme that is frankly preposterous and requires so much beyond their control to play out in a very specific way they could never guarantee…but we (rightly) love it because of the chutzpah involved in pulling it off and the brilliance of the reversal that lays it all plain.

“Silly” is usually a synonyms for “does not fit” in my mind, but equally the more out of left-field an idea comes, and the more risky the play, the more I tend to love it. So perhaps I’m not the best adjudicator.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve known ATTWN longer than any other GAD mystery, as it was the first I ever read. I often ponder the point you make here. The killer states that they planned to kill people in order of guilty conscience! But how much control could the killer possibly have? How could they be sure the General would isolate himself or that Blore would be the one to walk up to the house or that he would stand under the bear or that the octopus would be so gullible or that Vera would scream when the seaweed hit her or that Lombard and Vera would just say “screw it” and go back to the house and open a tin?

I think the book I would like to write is an Evelyn Hardcastle sort of thing where the ATTWN plan keeps going wrong, and the killer keeps doing it over . . .

LikeLike

I strongly agree about ATTWN even though I love it unreservedly, but yes, many of the plot elements are ridiculous. How did the killer manage to keep a BEE alive and contained, ready to place at the correct time without 1) getting stung or 2) getting noticed? For that matter, how could they be SURE the doctor would bring a syringe?

But the biggest plot weakness is that, like stupid characters in a B horror movie, it takes far, FAR too long for the characters (after five murders) to come to their senses, stop going off alone, and band together as a group for safety.

I would argue that a mystery writer has the hardest time overcoming suspension of disbelief, because they have to pull off the impossible plot that’s still at least somewhat grounded in the realm of the plausible world. You come to a horror novel, or a fantasy, etc. prepared to accept fantastical elements. I don’t think the mystery writer gets the same free pass-yet Christie nails the SOD challenge far more than she fails. Even in a novel as fantastical as ATTWN.

LikeLike

True, Richard, but let me address a few of your concerns regarding ATTWN:

1. How did the killer managed to keep a BEE alive and contained . . .”

There’s a shop in London called Red Herrings that will place live animals in small containers for you so that you can use them for such a purpose. The killer in Death in the Clouds shopped there too. (They also wrap fish. Delicious!)

2. How could they be sure the doctor would bring a syringe?

The doctor had been invited by U. N. Owen to take care of the neurotic hostess. He was bound to bring a complete medical kit.

3. . . . like stupid characters in a B-Horror movie . . .

I think perhaps civilized 1930’s British people take a longer time to admit there’s a killer in their midst. I’d have a hard time eating if everyone was dying around me, but they keep cracking open the tins . . .

LikeLike

Oh P.S.-another weakness is that it also takes too long (after 3 murders and a thorough search of a not that big island) for the characters to wake up and 1) fully accept that the deaths are murders and 2) that the killer is among themselves and not an outsider.

LikeLike

Oh, man, are we going to end up tearing ATTWN down? I’m almost tempted to reread it from the perspective of someone looking to dislike it and pick out its flaws…but, well, where’s the fun in that? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of these days I’ll join that GAD group, and waste hours archive trawling. But alas, I want to keep my soul from Zuckerberg as long as possible.

Sadly, I don’t really have a good answer to the silly solution question, more due to the lack of memory of the books I’ve read. I do think that quite a few solutions in mystery fiction are “silly,” but the skill of the authors is in convincing us that this is plausible, or at least that it is plausible in this context with these characters who act this way.

On a side note, I think I recall why the clocks were there in The Clocks. Kinda. They have so little to do with anything that I don’t understand why Christie put them in, or why the culprit though they would help! If it weren’t for them, I do think that The Clocks might be considered a decent late-stage Christie.

LikeLike

The problem is deeper and broader. Ghosts at banquets, witches, floating daggers and ineradicable spots, Birman wood on the march? How silly can a play get?

It’s all this make believe at fault. What we want sir, as Thomas Gradgrind so eloquently demands, is facts sir, facts.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Gradgrind’s a villain, Mr. Ken! A villain, sir! And when did we start talking about the Scots play? Did Sondheim write the Scots play???

I just noticed you’re Ken B. And I’m Bradley K (for Kenneth) – could we have been switched at birth?

LikeLike

Switched at birth? Hmmm. It depends. Are you the heir to a great fortune?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes and yes and yes to what you say Brad. Of course it’s a personal thing, what we are willing to accept from a writer (as it is in opera and Shakespeare plays, both full of sillinesses.) But ATF is a great favourite of mine too: I love the motive (sometimes described as inadequate – rubbish), and actually I can quite imagine that particular person having a sudden mad thought that they could carry off the plot in the book: ‘Yes I could! What the Hell! I will!’

I divide my Agathas into the good ones (huge majority) and some mis-hits: Elephants, Posterns, Destination, Frankfurt, and some early ones, And I am quite happy with the solutions of most of your (non-elephant) silly-picks above. But I agree on Clocks, which is almost unique in my categorization: it should be really good, it has all the trappings of her good books and none of the weaknesses of the bad – but it is disappointing and unsatisfying.

Oh the joy of discussing all this!

LikeLike

Pingback: #26 – Murder in Mesopotamia – WITH SPOILERS – Countdown John's Christie Journal

Pingback: #26 – Murder in Mesopotamia – Countdown John's Christie Journal

I think the key question is whether the element is silly enough that it spoils the book for the reader (and different readers will have different limits to their credulity). In the case of Sparkling Cyanide, I’ve always found the issue so distractingly unbelievable that I can’t stop thinking about it. Murder in Mesopotamia also requires you to believe something jaw-droppingly implausible, but since it’s otherwise such an excellent book, I’ve always given it a pass. However, since you pointed out in another post (Pondering the Impossible) the fact that the circumstance is not only silly, but also completely unnecessary to the plot and could easily have been left out of the story, I’m now viewing it with a more critical eye.

LikeLike